Rhododendron maximum

|

|

Photo Courtesy Renee Brecht |

Britton & Brown |

| Botanical name: | Rhododendron maximum |

| Common name: | great laurel |

| Group: | dicot |

| Family: | Ericaceae |

| Growth type: | tree shrub |

| Duration: | perennial |

| Origin: | native |

| Plant height: | 5 - 40' |

| Foliage: | Large leaves fine-woolly beneath, larger than Mountain Laurel |

| Flower: | Wide, open-funnel flowers, 1-1/2 to 2" wide; pink or white flowers with spotted green or orange. Flower stems sticky. |

| Flowering time: | late June to late July; fruits early August into Autumn |

| Habitat: | cool, moist ground of woods, watersides; occasionally in bogs of pinelands |

| Range in New Jersey: | scattered through north Jersey, most frequent near the Delaware River; rare on the Inner Coastal Plain and into the adjacent Pine barrens |

| Heritage ranking, if any: | n/a |

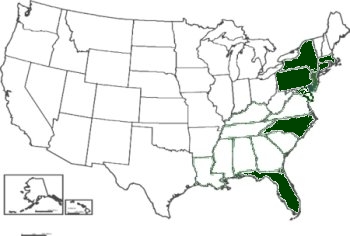

| Distribution: |  |

| Misc. | Witmer Stone, in 1910, states, "Along streams and lakes at various

points in the northern counties and down the Delaware to Florence

Heights. Also at two isolated localities in Cedar Swamps in the Pine

Barrens. The occurrence of the Rhododendron in the flat plains of the Pine Barrens has always been a surprise to me. Associated as it is in my mind with cool shaded slopes of the mountains, it seems entirely out of place in South Jersey. Pursh seems to have been the first one to have recorded its occurrence here, as he mentions under the habitat of the species "Shady Cedar Swamps, New Jersey, and Delaware". The stations are remote and not easy of access, so that the plant is not threatened with annihilation as it would be in more frequented spots. On July 9, 1910, I visited a colony near Sicklerville. My own efforts on a previous trip having failed to discover it, I was fortunate in obtaining directions from a native who had been to the "Oleander patch" several times. Entering a low wood I walked for perhaps two hundred yards on a gradual descent until I reached a point where white cedars began to appear and soon the ground pitched steeply down to the characteristic sphagnum bottom of the cedar swamp, with great rank growths of ferns, Woodwardias, Osmunda cinnamomea and Dryopteris simulata. The cedars rose on every hand like tall columns, their dense tops shutting off much of the light, and under them, with tangled and twisted trunks and branches, grew the Rhododendrons, the masses of white blossoms standing out conspicuously against the dark leaves and the general gloom. The high humidity, the absolute lack of motion in the air, and the low basin-like character of the spot made it extremely oppressive and the atmosphere seemed fairly reeking with moisture. I have suffered from excessive perspiration in the Rhododendron thickets of the Alleghenies much as I did that day in the cedar swamp, and perhaps the similarly humid conditions are what the plant needs. It was interesting to note growing with it another straggler from the north, Ilicioides mucrinata, brought evidently by the same climatic upheaval which drove the Rhododendron so far to the south of its usual range. The swamp stretched away on all sides, and one might wander for hours through its gloomy depths without finding this little thicket, or without finding the way out again if it were not for the path that had been opened up by woodchoppers. Another larger patch of Rhododendrons has been seen by gunners in wither time in the swamps bordering the upper Egg Harbor River, but I could find no one who had visited it in summer, and those who had stumbled upon it in autumn or winter could not find their way back again" (614-615). |